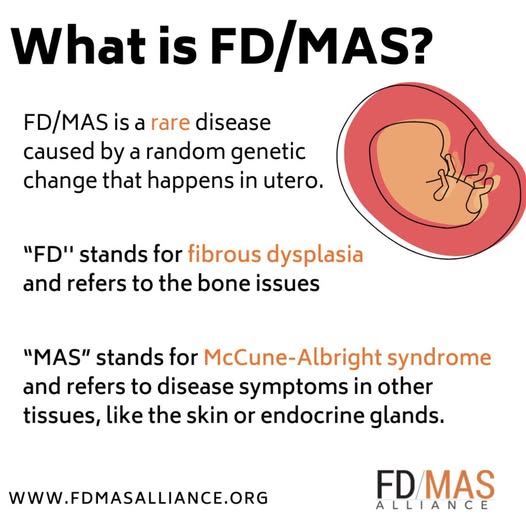

What is FDMAS?

FDMAS stands for Fibrous Dysplasia / McCune–Albright Syndrome. It’s a spectrum of a rare genetic condition caused by a post-zygotic (mosaic or in-utero) mutation in the GNAS gene.

What it is

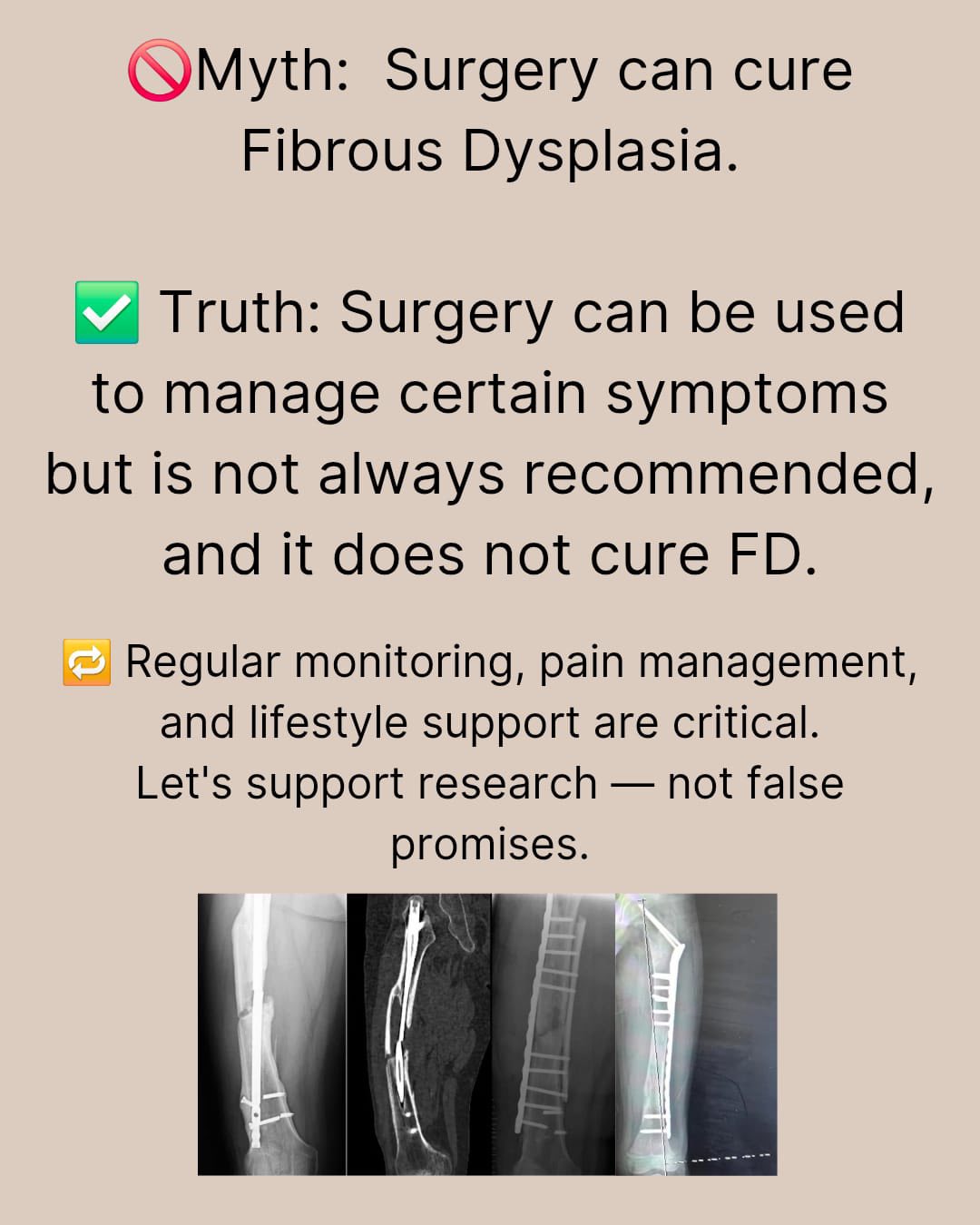

Fibrous Dysplasia (FD): Normal bone is replaced by fibrous (scar-like) tissue, making bones weaker, prone to deformity, pain, or fracture. It can affect:

One bone (monostotic FD) — this is what I have (craniofacial monostotic FD)

Multiple bones (polyostotic FD)

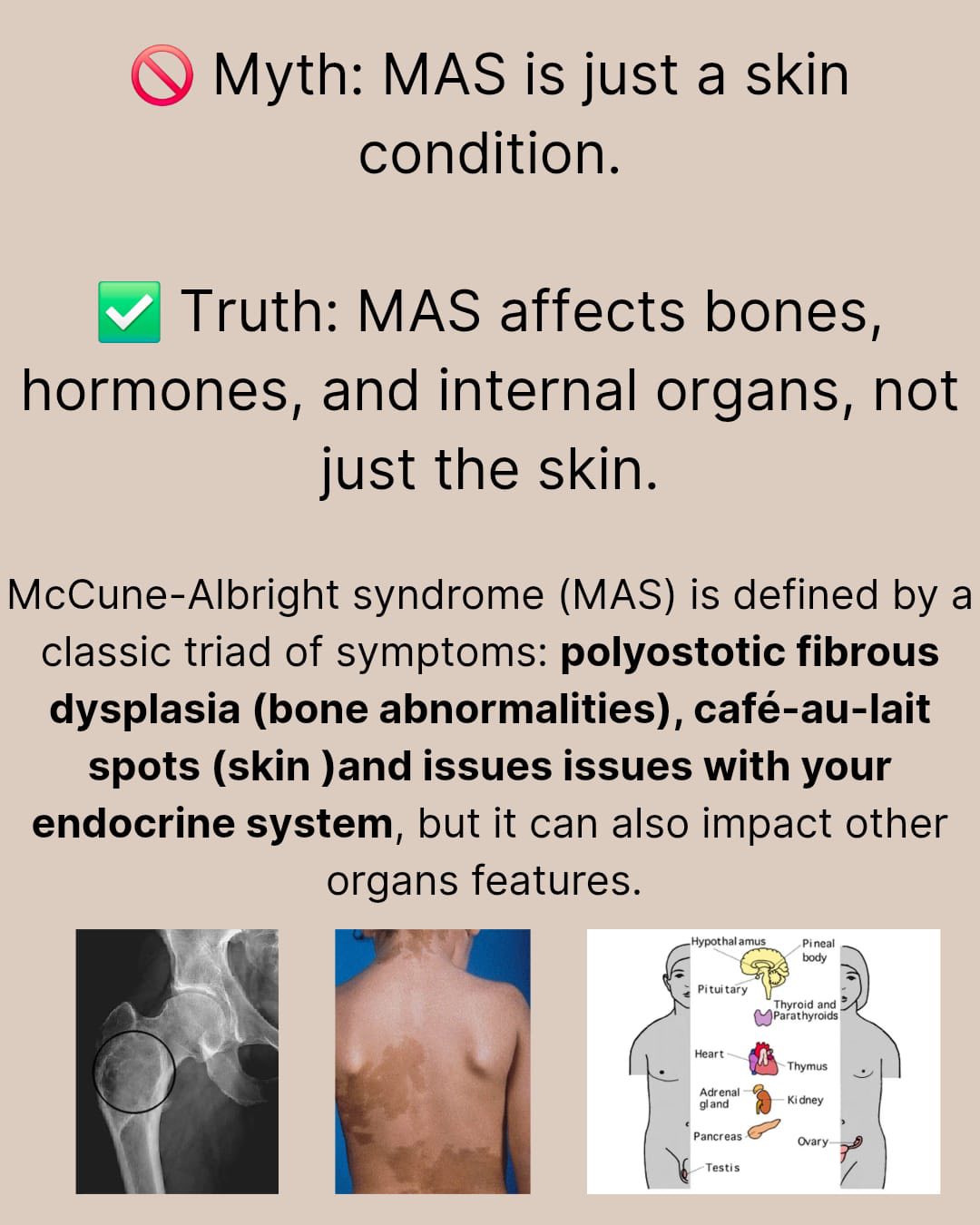

McCune–Albright Syndrome (MAS): The more complex form of FDMAS that includes:

Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia

Café-au-lait skin spots (often irregular “coast of Maine” borders)

Endocrine overactivity, such as:

Early puberty

Thyroid problems

Growth hormone excess

Cushing syndrome (rare)

Not everyone with fibrous dysplasia has MAS — MAS is the endocrine/skin + bone combination. I’m grateful that I “only” have FD, not MAS, but not everyone is as lucky as me!

#FDMASGlobalAwarenessWeek is a coordinated international campaign to raise awareness of #mccunealbrightsyndrome #FDMAS and build support for public health and research efforts that improve the lives of the community.

We start on the 20th of the month because the mutation that leads to both #FD and #MAS is found on the 20th chromosome.

We celebrate for a full week because it is a complex, diverse, chronic, incurable condition that occurs in all populations. We have a lot to share! We culminate on #RareDiseaseDay because we share so many experiences, challenges, and hopes with others in the Rare Disease community. We invite you to join us! https://fdmasalliance.org/global-awareness-week/

How rare is FDMAS?

Fibrous dysplasia (all forms):

Estimated at ~1 in 15,000 to 1 in 30,000 people.McCune–Albright syndrome:

Much rarer — about 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 1,000,000 people.

Why FDMAS happens

Caused by a somatic (not inherited) mutation in the GNAS gene.

It happens early in embryonic development.

Because it’s mosaic, the severity depends on:

When the mutation occurred

How many cells/tissues were affected

It is not usually inherited, and parents did nothing to cause it.

Is FDMAS life-threatening?

Most cases are not fatal, but complications can occur:

Bone deformities or fractures

Craniofacial involvement (vision/hearing issues in severe cases)

Endocrine complications if MAS is present

Management usually involves:

Endocrinology

Orthopedics

Imaging follow-up

Sometimes bisphosphonates for bone pain (which have their own side effects)

Why Do I Care about FDMAS?

In 2019, my skull was screaming with pain and pressure, with a visible lump on the side of my cheekbone/temporal area. I had no idea what was wrong, or what could possibly be causing the issue, just knew that this wasn’t right.

It turns out that for the past 30+ years I had been slowly growing a massive tumor. Ever since I was a fetus developing in my mom’s uterus, I had cells in my skull that had a GNAS mutation, causing the immature skull cells to remain spongey and soft, rather than the usual hard, protective cells that most people have in their skull. Luckily, I never played contact sports other than in gym class…if I had, and that place was hit during a game, I could have died. No exaggeration. Super, super lucky.

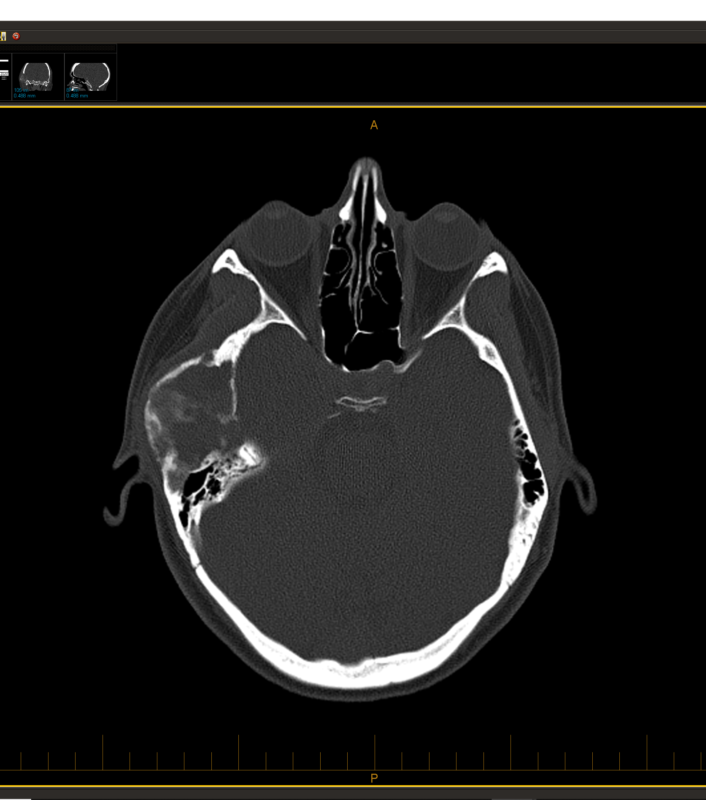

By July 2019, I had had enough. I sought out a doctor who would listen and order CT scans — my primary doctor thankfully was willing to investigate. While it appears that they may have confused my chart with someone else (the nurse at first told me I have nasal polyps, which I do NOT have), it was clear to me that I had a large tumor in my skull. This is part of being your own best advocate as a patient — go pick up your test results and look at them yourself, like I did. I learned a LOT about radiology analysis that week, comparing my scans with others on educational sites.

With my husband Don supporting me (and his Entrepreneurs Organization connections getting me in touch with the best skull-based surgeon in the state, who had arrived in OK only a few months before my surgery), I saw several specialists ranging from neurosurgery to orofacial and plastic surgery to ear nose throat surgery. My surgery team of 3 planned out the delicate procedure, concerned that I might lose hearing in my right ear if the tumor impinged on the ear canal, perhaps end up with severe paralysis in my face if the trigeminal nerves were too entangled, and maybe my jaw would need replacing on that right side. At the time, the surgeons thought I might have a hemangioma. But based on the radiology scans, I wondered if it was FD (fibrous dysplasia), due to the shattered glass-like look.

November 2019: my 6-hour resection surgery was successful…and I awoke with full hearing, a temporarily-wired jaw that they undid just as quickly when they realized my jaw wasn’t affected by the tumor, a new cheekbone made of metal, bone from the back of my skull, and fat from my belly. Yeah, my cheekbone had been devoured by the spongey tumor, but thankfully I had an awesome plastic surgeon — my face today is WAY more symmetrical than it’s ever been before!

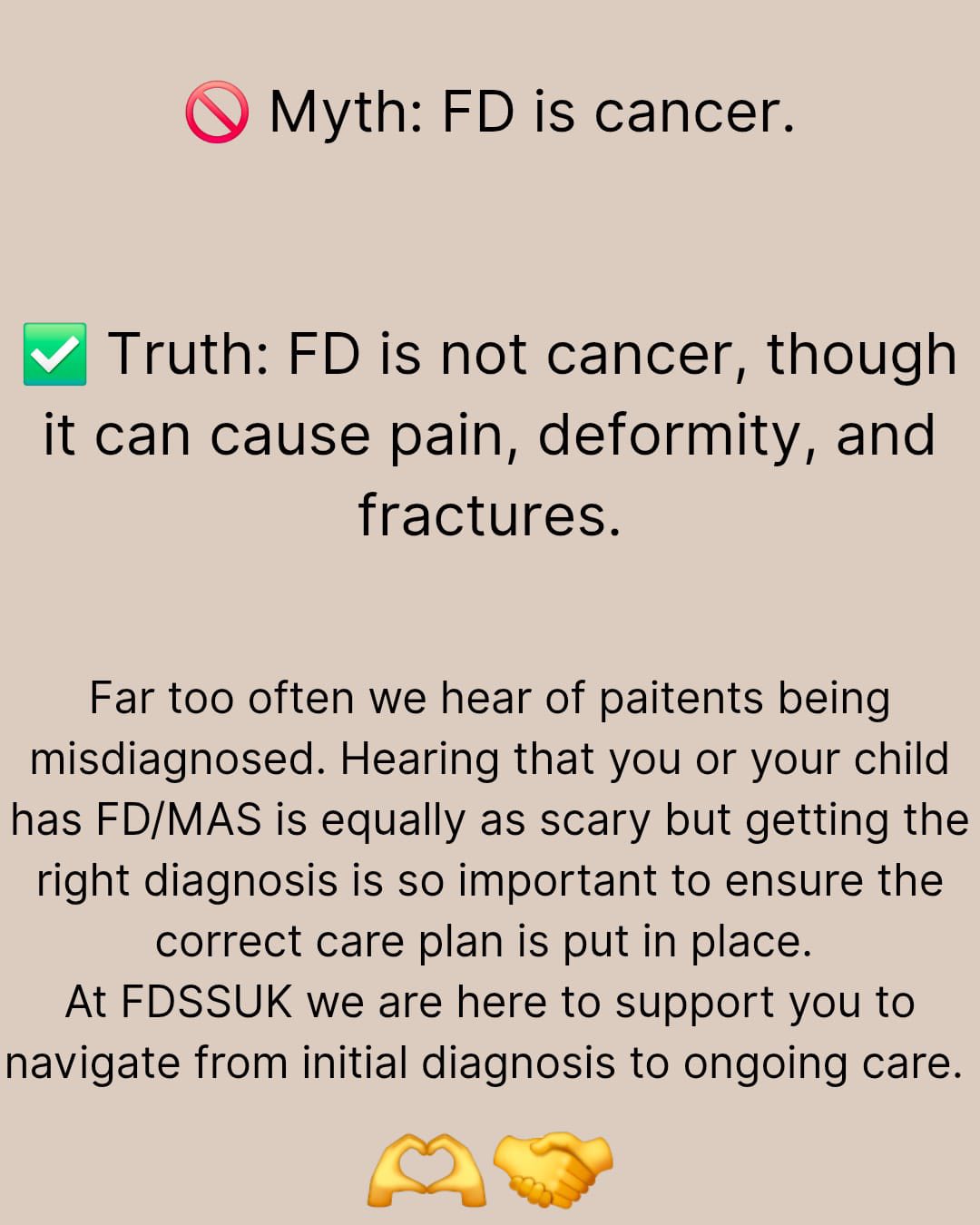

Diagnosis: Monostotic Craniofacial Fibrous Dysplasia — non-cancerous, spongey tumor that ate my cheekbone and was 1 mm from making me deaf in my right ear.

7 years later, I do have some minimal facial weakness on the right side, such that my mouth drops a little sometimes. But considering what it could have been, I’ll take this minor inconvenience that I only notice when I’ve been sleeping. And the trigeminal nerves still sit barely below the skin over my ear, which can hurt to touch. But the scars have mostly disappeared, leaving little trace of the traumatic surgery I survived. Today, unless I say something, no one has any idea of what I experienced.

As I said, I’m incredibly lucky. With a new solid skull plate in place, my skull is protected once more. While I still have headaches like I’ve had my whole life, they no longer come with that weird “breathing” sensation that was so obvious in August of 2019. The tumor could return, if there were any cells left behind, but the surgeons were sure that they removed enough that even if a few cells remained, it would take another nearly 40 years to grow enough to cause issues again.

Not everyone with FDMAS is as lucky as I was. Some children are disfigured for life, dealing also with hormone issues. Surgery may not be an option for them, as sometimes when you disturb the tumor, it can grow more. Others have the tumor in areas that could cause severe complications if removed. My case was the best case scenario, and I’m fully aware of my incredible good luck, especially after being part of FD advocacy groups, seeing what others must deal with year after year, with little to no relief.

FDMAS is a rare disease — normally, if a doctor sees a tumor like this, they think “horse”, not “zebra”. But I’m a zebra, like many others across the world. Sometimes the obvious answer isn’t obvious. Today, we need better studies and research money to understand this unusual disease, if we are to have any hope of treating and potentially curing others. If you’re looking for a worthy cause to support, please contribute to nonprofits like FDMAS Alliance.